Digestive issues are common, affecting up to 70 million Americans, but that doesn't make them any less alarming. If symptoms like abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloating, or even blood in stool start to interfere with your patient's daily life, it's natural to worry—and you may want to rule out more serious conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or colorectal cancer. A noninvasive stool test called calprotectin can help you do this.

[signup]

Understanding Calprotectin

Calprotectin is a protein released by white blood cells, specifically neutrophils, during active inflammation.

Unlike other systemic inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), calprotectin is released into the gut lumen and subsequently excreted in feces in response to inflammatory processes in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

Its concentration correlates with the degree of intestinal inflammation, making it a valuable noninvasive tool for distinguishing inflammatory bowel pathologies (like IBD) from non-inflammatory conditions and monitoring disease activity.

Why Does It Matter?

Because fecal calprotectin levels correlate with endoscopic and histologic inflammation, it is a valuable tool for distinguishing IBD from non-inflammatory conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), monitoring disease activity, assessing mucosal healing, and predicting patient response to IBD therapy.

Fecal calprotectin has a high negative predictive value, meaning a normal level reliably excludes active IBD in symptomatic patients. Therefore, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recommend fecal calprotectin as an adjunct to clinical and endoscopic assessment for differentiating IBD from IBS and monitoring disease activity.

Calprotectin Test Overview

The calprotectin test is a stool test that measures how much calprotectin is present in a fecal sample. It is:

- Noninvasive, requiring only a small stool sample

- Sensitive to intestinal inflammation, especially in the colon

- Useful in identifying whether symptoms like diarrhea or abdominal pain are caused by inflammatory conditions

Use this test as an early step to decide whether more invasive procedures, like a colonoscopy, are necessary. Order this for patients with symptoms like:

- Persistent diarrhea

- Abdominal pain and cramping

- Blood, mucus, and/or pus in stool

- Feeling like you always need to have a bowel movement

- Fecal urgency

- Unintentional weight loss

For patients with IBD, this test can also be used as a noninvasive and cost-effective method for monitoring the condition and assessing whether treatment is working.

How the Test Works

The calprotectin stool test is painless and poses no risk, making it a convenient first step in evaluating digestive symptoms.

The collection process is simple. Guide patients to:

- Label the container with their name, along with the date and time of collection.

- Use the kit to collect stool. Catch the sample in a clean collection "hat" placed over the toilet bowl or using plastic wrap stretched across the seat.

- Open the specimen container and transfer the recommended amount of stool into it using the stick or spoon provided. Be careful not to touch the inside of the container or allow the sample to come into contact with other surfaces.

- Seal the container tightly and return it to the lab as soon as possible.

- Wash their hands thoroughly with soap and water after handling the sample.

Preparing for the Test

One of the benefits of this test is that it requires little to no preparation.

Clinical data demonstrate that certain medications can lead to mild-to-moderate elevations in fecal calprotectin. Therefore, you may want to recommend that patients stop taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for 2-3 weeks before collecting their stool sample.

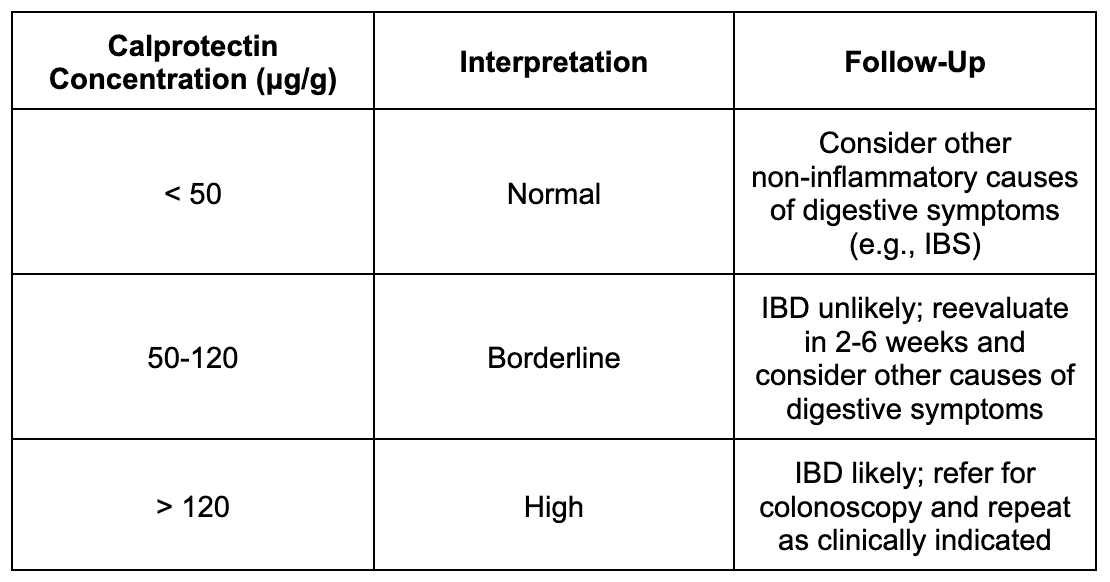

Interpreting Results

Calprotectin is measured in micrograms per gram (μg/g).

What the Numbers Mean

The table below shows what different calprotectin levels mean and what steps are typically recommended based on results.

Conditions That Raise Calprotectin

Fecal calprotectin detects and quantifies intestinal inflammation; however, it is nonspecific (it can't tell you exactly what's causing the problem). Additional tests and imaging will be required to diagnose the underlying cause of elevated calprotectin levels.

Possible causes of high calprotectin include:

- Inflammatory bowel disease, encompassing Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis

- Viral and bacterial gastroenteritis

- Celiac disease

- Diverticulitis

- Drug-induced intestinal inflammation

- Intestinal malignancy

- Pancreatitis

Calprotectin in Diagnosis and Monitoring

IBS and IBD frequently present with overlapping GI symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloating, making symptom-based diagnosis unreliable for distinguishing between these conditions. The absence of specific biomarkers for IBS further complicates differentiation, especially in patients with diarrhea-predominant or mixed subtypes.

Differentiating Between IBD and IBS

Sensitivity, which measures how well a test detects people who do have a disease, ranges from 78.3% to 91%. This means fecal calprotectin correctly identifies most people with IBD.

The test is also very good at identifying people without the disease. Pooled data demonstrate the test has a specificity of 91.7% and a negative predictive value of 99.8%. This means that adults with calprotectin less than 50 μg/g are unlikely to have IBD.

Compared to serologic markers like CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), fecal calprotectin demonstrates superior diagnostic accuracy for distinguishing IBD from IBS. CRP and ESR may be normal in up to 40% of IBD patients, particularly those with mild disease.

A normal fecal calprotectin level in a patient with typical IBS symptoms and no alarm signs can reliably exclude IBD, reducing unnecessary specialist referrals and colonoscopies when ordered in both primary care and gastroenterological settings.

Monitoring IBD Activity

In established IBD, fecal calprotectin levels correlate closely with endoscopic and histologic inflammation, making it a valuable noninvasive tool for monitoring disease activity and mucosal healing. Serial fecal calprotectin measurements are increasingly used to assess response to therapy, detect subclinical inflammation, and guide treat-to-target strategies.

Specific calprotectin cut-offs have been associated with IBD outcomes and are used for clinical decision-making. For example:

- Fecal calprotectin < 60 μg/g predicts disease remission

- Fecal calprotectin < 187 μg/g predicts mucosal healing

- Fecal calprotectin > 321 μg/g in patients in clinical remission predicts a higher risk of relapse within six to 12 months.

The AGA guidelines for ulcerative colitis note that patients in symptomatic remission but with elevated fecal calprotectin have an estimated annual relapse risk of 64%, compared to 15% in those with normal fecal calprotectin. Therefore, incorporating routine fecal calprotectin measurement into IBD management may improve predictive accuracy for patient relapse and guide appropriate treatment decisions.

Limitations and Considerations

The following considerations should be taken into account when interpreting calprotectin test results.

Age

Fecal calprotectin levels are physiologically higher in infants and young children, especially under 1 year of age, with median values several-fold higher than in older children and adults. After the first year of life, levels decrease and stabilize, with no significant difference between older children and adults.

In older adults (≥65 years), the specificity of the test decreases, and elevated calprotectin may be seen in the absence of IBD, likely due to age-related gut changes and comorbidities.

False Negatives

The accuracy of the fecal calprotectin test can vary depending on the situation and which cutoff value is used to define a "normal" result.

According to the AGA guidelines, in patients with ulcerative colitis, the false negative rates for fecal calprotectin cutoffs of <50 μg/g, <150 μg/g, and <250 μg/g are 11.0%, 14.5%, and 18.5%, respectively. This means that a notable number of patients may still have active inflammation, even if their test result appears normal, highlighting that the test can sometimes miss ongoing disease.

Similarly, in patients with Crohn's disease at a higher risk for active inflammation, the AGA guidelines report false negative rates of 9.6%, 15.2%, and 19.2% for the same cutoffs listed above.

Test Limitations

Fecal calprotectin is a nonspecific marker of neutrophilic inflammation and can be elevated in a range of conditions beyond IBD. It does not distinguish between different causes of inflammation.

Sample handling, extraction methods, and assay variability can affect fecal calprotectin levels. There is also intra-individual and day-to-day variability, so repeat testing may be necessary to confirm results.

Fecal calprotectin may be normal or borderline in mild disease. Due to physiologically higher levels, higher thresholds may also be needed in children under two, older adults, and people who are overweight.

Although fecal calprotectin levels mirror the degree of inflammation seen on endoscopy or biopsy, the test can't show how far the disease has spread, identify complications, or provide a definitive diagnosis. It should complement, not replace, endoscopy and must be interpreted alongside other labs, imaging, and the patient's overall clinical picture.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What does a high calprotectin level mean?

A high calprotectin level suggests intestinal inflammation from conditions like IBD, infection, or colorectal cancer.

Can IBS raise calprotectin levels?

Not typically. Calprotectin is usually low in IBS, which is non-inflammatory in nature.

Can diet affect the test?

Evidence indicates that certain food intolerances or malabsorption syndromes are associated with elevated fecal calprotectin, and that targeted dietary interventions addressing these intolerances can significantly reduce fecal calprotectin concentrations.

Can stress affect the test?

Stress does not appear to directly affect fecal calprotectin levels. Studies in adults and children have found that while perceived or chronic psychosocial stress is associated with increased GI symptoms, it is not associated with elevations in fecal calprotectin or objective intestinal inflammation.

Is the test painful or risky?

No. It is completely noninvasive and risk-free.

How long does it take to get results?

Typically 4-5 days, depending on the lab.

[signup]

Key Takeaways

- Calprotectin is a protein released by white blood cells (neutrophils) during inflammation in the GI tract. The calprotectin stool test is a noninvasive way to measure this protein to detect intestinal inflammation.

- This test is recommended for patients with persistent GI symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, bloating, or unintentional weight loss. It is beneficial in cases where IBD needs to be distinguished from non-inflammatory conditions like IBS.

- Fecal calprotectin correlates closely with endoscopic and histologic inflammation, making it valuable for assessing mucosal healing, monitoring treatment response, and predicting relapse.

- The test cannot determine the exact cause or location of inflammation, false negatives can occur, and factors like medications and age can influence results.

- Fecal calprotectin is a reliable, evidence-based tool for assessing intestinal inflammation. It is not a standalone test but should be interpreted alongside symptoms, physical findings, other labs, imaging, and endoscopy.

%201.svg)