Vitamin B12 deficiency is more common than many people realize. It affects about 6% of individuals under 60, with the prevalence rising to 20% in those over 60. Although the symptoms can be subtle at first, this vitamin deficiency can be detrimental to overall health. Despite how widespread it is, many remain unaware of the risks, symptoms, and potential consequences of low B12 levels.

[signup]

What's Vitamin B12?

Vitamin B12 is one of the eight water-soluble B vitamins. It is unique in that it contains cobalt in its chemical structure. For this reason, "cobalamin" is used to refer to compounds that have B12 activity. Methylcobalamin and 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin are the two metabolically active forms used in the human body.

Role of Vitamin B12 in the Body

Vitamin B12 is required for the development and function of the central nervous system; healthy red blood cell (RBC) formation; and DNA synthesis.

Methylation

Methylation is the biochemical process that involves adding a methyl group (CH3) to a substrate, such as DNA, proteins, or other molecules, to influence gene expression and protein function.

Vitamin B12 (in the form of methylcobalamin) acts as a cofactor for the enzyme methionine synthase, which catalyzes the conversion of homocysteine to methionine. Methionine is an amino acid precursor to S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe), which acts as the primary methyl donor in the body.

DNA Synthesis

The regeneration of tetrahydrofolate (THF) from 5-methyltetrahydrofolate relies upon the conversion of homocysteine to methionine by methionine synthase. THF is a derivative of folic acid that acts as a coenzyme for producing thymidylate, a nucleotide required for DNA synthesis.

Thymidylate synthesis is a rate-limiting step in DNA replication and repair. When vitamin B12 levels are insufficient, the methionine synthase reaction is disrupted, leading to a phenomenon called the "methyl-folate trap." In this state, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate accumulates, and THF becomes depleted. This depletion impairs the synthesis of thymidylate and purines, both essential for DNA synthesis and repair, resulting in genomic instability.

Neurological Function

Vitamin B12 helps form and maintain myelin, the protective sheath around nerves, which facilitates nerve signal transmission.

Red Blood Cell Formation

5-Deoxyadenosylcobalamin is a cofactor for L-methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, the enzyme that converts L-methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA. Among other functions, succinyl-CoA is involved in making hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in RBCs.

RBCs also require vitamin B12 to grow and develop into mature, fully functioning cells. A deficiency can lead to fewer larger-than-normal RBCs in circulation (megaloblastic anemia).

Sources of Vitamin B12

Since the body cannot produce vitamin B12, it must be obtained from food or supplements.

Dietary Sources

Vitamin B12 is primarily found in animal-based foods, including meat, poultry, fish, dairy products, and eggs.

Most plant-based foods do not naturally contain vitamin B12, but some exceptions exist, such as fermented beans and vegetables, edible algae, and mushrooms. Additionally, cereals and nutritional yeasts may be fortified with bioavailable vitamin B12.

Supplements

Vitamin B12 is available over the counter as a single nutrient or as a component of multivitamin/mineral and B-complex supplements.

Cyanocobalamin is the most common form of B12 in dietary supplements, but other forms include adenosylcobalamin, methylcobalamin, and hydroxycobalamin.

Causes of Vitamin B12 Deficiency

Insufficient dietary intake, malabsorption, congenital disorders, and certain environmental exposures cause vitamin B12 deficiency.

Dietary Insufficiency

Individuals who follow vegan and vegetarian diets are at a higher risk of B12 deficiency because plant-based foods generally do not contain vitamin B12, and fortified foods may not provide enough to meet nutritional needs.

Pregnant and breastfeeding women require more B12 to support fetal and infant development. If they do not get enough from their diet or supplements, they may develop or pass on a deficiency to their baby.

Malabsorption

Even with sufficient intake of B12, the body must be able to absorb it effectively:

- B12 is released from food proteins in the stomach by digestive enzymes, then binds to a protein called haptocorrin.

- In the small intestine, pancreatic enzymes release B12 from haptocorrin, allowing it to bind to intrinsic factor (IF), a protein produced by specialized cells in the stomach lining called parietal cells.

- This B12-IF complex travels to the ileum (the final portion of the small intestine), where specialized receptors on intestinal cells facilitate its absorption into the bloodstream.

Various conditions can interfere with B12 absorption:

- Pernicious anemia is an autoimmune condition in which the body makes antibodies that attack parietal cells and block the action of IF.

- Gastrointestinal conditions such as celiac disease, Crohn's disease, and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth can impair B12 absorption, leading to deficiency over time.

- Certain surgeries, such as gastric bypass or removing parts of the intestines, can lead to a complete or partial loss of sections of the digestive tract that are necessary for absorbing vitamin B12.

- Alcoholism can lead to intestinal damage that impairs B12 absorption.

Congenital Disorders

There are rare genetic disorders that can lead to vitamin B12 deficiency. These conditions are caused by gene mutations that affect proteins involved in B12 absorption, transport, and processing within cells. Examples include:

- Congenital pernicious anemia affects the synthesis of IF

- Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome affects B12 absorption in the ileum

- Transcobalamin II deficiency affects the transport of B12 throughout the body once it has been absorbed

Environmental Exposures

Nitrous oxide (commonly known as "laughing gas") inactivates vitamin B12 and can produce clinical symptoms typical of vitamin B12 deficiency.

Certain medications can deplete vitamin B12 levels, including:

- Proton pump inhibitors

- Oral contraceptive pills

- Metformin

Vitamin B12 Deficiency Symptoms

Vitamin B12 deficiency can cause physical, neurological, and psychological symptoms. Because other health conditions can share these symptoms, a proper diagnosis requires clinical evaluation and laboratory testing to rule out other possible causes.

Anemia

B12 deficiency can cause megaloblastic anemia, resulting in symptoms like:

- Fatigue

- Cold hands and feet

- Pale skin

- Shortness of breath

- Heart palpitations

- Dizziness

- Headache

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

- Numbness and tingling in the hands and feet

- Difficulty walking

- Confusion

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Memory loss and dementia

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

- Glossitis (inflammation and pain of the tongue)

- Loss of appetite

- Changes in bowel habits

Diagnosing Vitamin B12 Deficiency

Initial laboratory evaluation for patients at high risk for or with clinical symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency includes the following blood tests:

- Complete Blood Count: to rule out macrocytic anemia

- Serum Vitamin B12: a level less than 150 pg/mL is diagnostic for deficiency

Additional testing of biomarkers that are more reflective of vitamin B12's physiologic activity is recommended for patients with borderline serum B12 levels or for those who may have artificially elevated serum B12 levels, which can occur in conditions such as alcoholism, liver disease, and cancer:

- Homocysteine: levels greater than 15 micromol/L suggest vitamin B12 deficiency. However, results should be interpreted carefully because homocysteine can also rise in the presence of folate deficiency and kidney disease.

- Methylmalonic Acid: levels greater than 0.271 micromol/L suggest vitamin B12 deficiency

Patients who have been diagnosed with vitamin B12 deficiency without apparent cause should be tested for pernicious anemia by ordering:

Treatment and Management

Vitamin B12 deficiency treatment involves B12 replacement.

Dietary Modifications

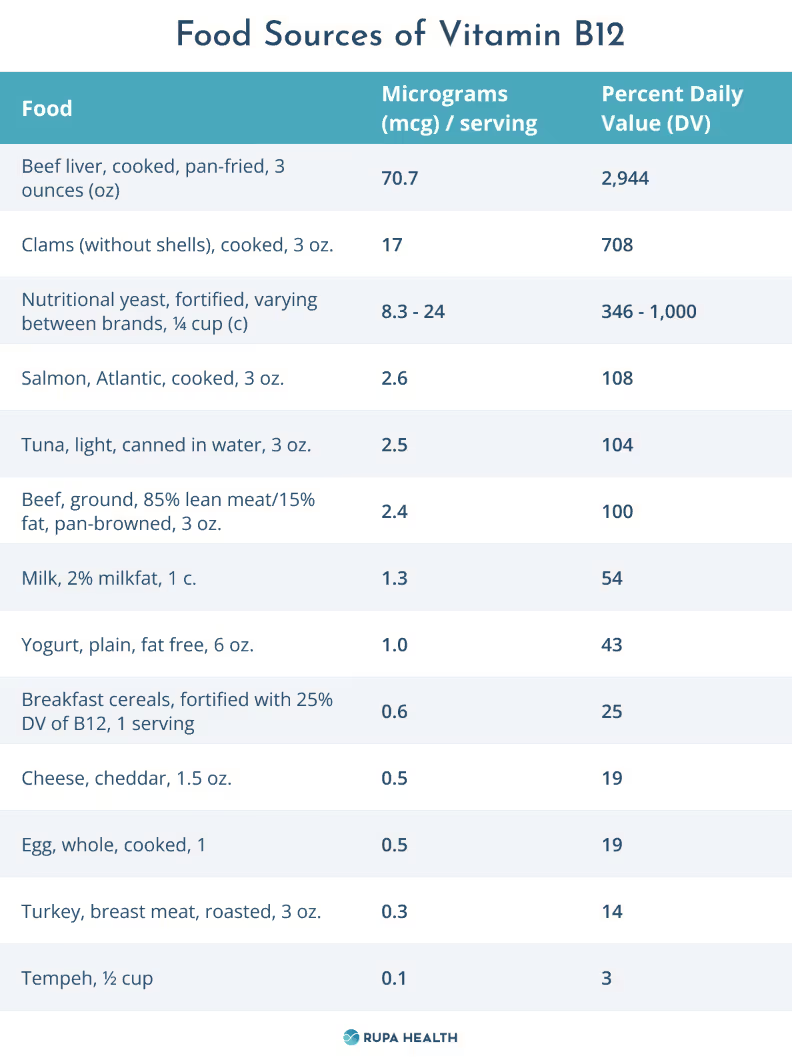

When possible, patients should be encouraged to incorporate B12-rich foods into their diet. Examples are listed in the table below:

Supplementation Options

Intramuscular or oral vitamin B12 replacement therapy will also be required for varied durations, depending on the cause and severity of the deficiency.

Intramuscular B12

Intramuscular therapy is recommended for patients with severe deficiency, pernicious anemia, and/or neurological symptoms.

- Acute Dosing: 1,000 mcg intramuscularly once weekly for four weeks

- Maintenance Dosing: Patients with IF deficiency should continue to receive 1,000 mcg intramuscularly once monthly

Oral B12

Cyanocobalamin is the most common form of vitamin B12 in oral dietary supplements, although methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin are the most active forms.

Oral dosing regimens vary depending on the severity and cause of vitamin B12 deficiency but generally range from 500-2,000 mcg/day in adults.

A 2005 Cochrane review found that high-dose (1,000-2,000 mcg daily) oral replacement was as effective as intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 for correcting anemia and treating neurologic symptoms.

Preventing Vitamin B12 Deficiency

Deficiency can be prevented by consuming the recommended daily allowance (RDA) of vitamin B12. RDAs vary by age and sex:

Risk Factors and Early Detection

Prophylactic vitamin B12 supplementation helps prevent deficiency from occurring in people at high risk of insufficiency. These populations include:

- Adults aged 65 and older

- Individuals with pernicious anemia

- Individuals with malabsorptive gastrointestinal disorders

- Individuals who have had gastrointestinal surgery

- Vegans and vegetarians

- Individuals who have been taking proton pump inhibitors for more than one year or metformin for more than four months

Routine screening is warranted for people with at least one risk factor for vitamin B12 deficiency to detect early signs of deficiency.

[signup]

Key Takeaways

- Vitamin B12 supports essential physiological functions, such as red blood cell production, neurological function, and DNA synthesis.

- Deficiency in this water-soluble vitamin can lead to a wide range of serious health issues, including megaloblastic anemia, cognitive decline, and nerve damage.

- Certain groups, including the elderly, vegetarians, vegans, and individuals with gastrointestinal disorders, are at higher risk for vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Dietary counseling and routine screening are the primary strategies for prevention and early detection in at-risk populations.

- Recognizing the signs of deficiency, including fatigue, neurological symptoms, and gastrointestinal issues, assists in early detection.

- Confirming the diagnosis with laboratory tests prevents long-term complications and ensures timely intervention with B12 replacement to restore health.

%201.svg)